‘The clock becomes a white skull grinning at him from the wall, its hands whirring like giant spiders . . .’

Anna Croissant-Rust

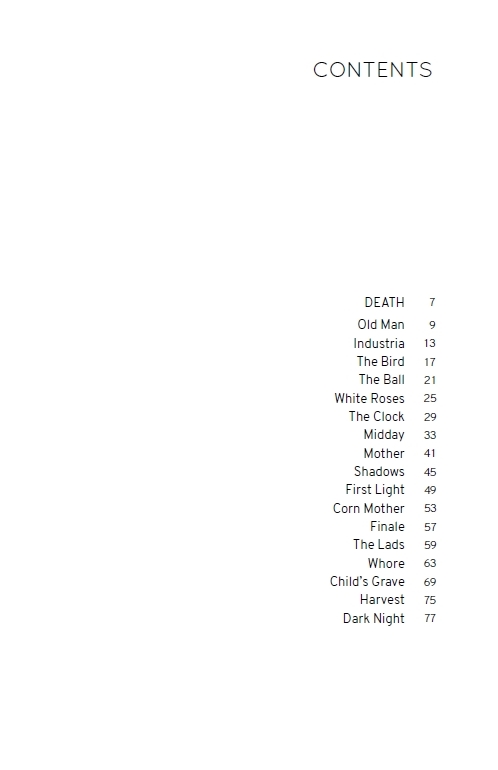

Death

Translated by James J. Conway

Design by Cara Schwartz

11 June 2018

170 pages, trade paperback

French flaps, 115 x 178 mm

ISBN: 978-3-947325-04-7

Distribution

UK/Ireland (Central Books)

US (SPD)

To the fretful mother of a sick child it comes in the form of the long-awaited doctor. To a feeble old man it arrives as an obliging stranger who helps him to his feet and out through the garden gate. To the hapless workers of an overtaxed factory it is an industrial disaster with a paranormal dimension. Death comes to them all, yet the stories in Anna Croissant-Rust’s cycle are charged with life. The ever-changing personification of mortality appears amid scenes of unexpected enchantment, full of light and wonder, of reverence for the mercurial passions of nature. An inventive revival of the medieval danse macabre, Death was issued in Germany on the eve of World War One. It is paired here with the author’s earlier collection Prose Poems, which fused free verse and fragmentary narrative to create something sublime and entirely original. The intense emotional register and singular style confounded critics when it was first published in 1893, and by the time other writers were producing comparable work in the early 20th century it had been forgotten. This major English-language debut confirms Anna Croissant-Rust as a hugely powerful writer well overdue for recognition.

DOWNLOAD free PREVIEW (PDF)

Even within her native Germany, Anna Croissant-Rust (1860-1943) remains an obscure figure. She spent most of her adult life in Munich, a highly valued contributor to the city’s literary life. In 1890 Croissant-Rust became the sole female member of the forward-looking ‘Society for Modern Life’. Her first three books, all issued in 1893, blended the Society’s house style of Naturalism with formal experiments for which there was little precedent, with an acute subjectivity that pointed ahead to Expressionism. While most of her later fiction and drama deployed more traditional story-telling modes, they were often rendered in regional dialect that lent them immediacy and authenticity. Common to all of her works is a profound engagement with natural forces and a tireless fascination for psychological motive. Poverty and illness brought Anna Croissant-Rust’s literary career to a premature halt around 1920, and she died in Munich in 1943.

related

External links

Beyond the veil (extract at Strange Flowers)

Often comprising only the last moments of each figure’s life, these stories are intense and unflinching spiritual investigations of dying as an experience that unfolds in life. Death is also a portrait of a society—like a medieval dance of death mural, it depicts people of all stations, urban and rural, old and young, male and female.

— Amanda DeMarco, Music & Literature

Death is a wild book. It’s wild — structurally, linguistically, sure; in particular, its mix of romantic 19th c. diction (torpor, imperious, etc) twisting into anarchic 20th c. syntax — but what I mean specifically is this: It reminds me of those rare encounters when you’re out for a run in the park, in the morning, and you turn down a path through the trees, and then, suddenly, there’s a coyote right there...

— Devin Smith, Full Stop

Morbid, sentimental, surreal, Rust breaks down narrative into patterns of feeling, abandoning any formal devices or logic. When someone describes a modern work as “dreamlike,” I think of Rust, who is, for me, the original dreamer; these are pieces written by ghosts, desperate to send a message to the living while at the same time utterly resigned to failure.

— Maryse Meijer, Electric Lit

Anna Croissant-Rust’s collection, Death, originally published in 1914 and coalescing moments of poetry and prose and experimenting in form, is equally compelling, a deeply adumbrated rumination on mortality, as the spectre of World War I and Germany’s apocalyptic fate draw ever nearer.

— Julian Tompkin, The Australian

Although most of the seventeen pieces are just a few pages long, their rich language and evocative prose give them an intensity and depth of longer works … I highly recommend this book. The stories are uniformly excellent and after reading this volume I left it for a week or so and then re-read them more slowly, a few tales a day. I found them just as enjoyable the second time out.

— Side Real Press

Dense, doomy, and delightful.

— an eudæmonist

FROM THE AFTERWORD

Compare the nun in ‘White Roses’ and the titular ‘Whore’; each remembers a formative encounter from her youth. For the nun it is the disappointment of lost love, for the prostitute a carnal initiation whose violence is only suggested. Then there are the gardens of ‘old-fashioned flowers’ in ‘Old Man’ and ‘Midday’ and their respective occupants, one deliberately forgetting the pains of the past, the other reliving its glories. Each story takes place in a compressed time frame, sometimes in what we can assume to be mere minutes, sometimes over the arc of a day or night. Only in one instance – ‘The Clock’ – can we narrow the action down to a named location – Munich – although there can be no doubt that the riverside factory city of ‘Industria’ is Ludwigshafen. Elsewhere the odd snatch of dialect in the original – such as the Austrian idioms in ‘The Lads’ – allows us to loosely localise the narrative.

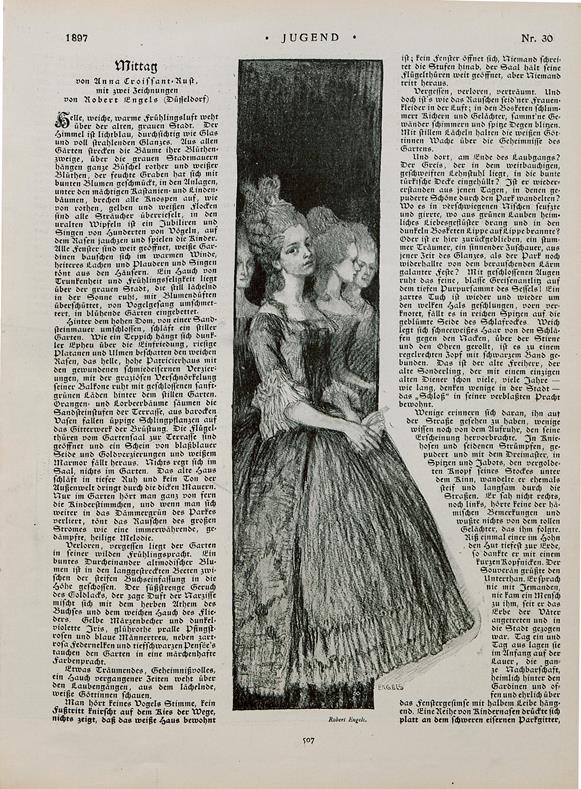

The anthropomorphism of Prose Poems returns here. While it is far from unusual to find writers fleetingly ascribing human traits to landscapes, weather phenomena and the animal kingdom – ‘treacherous terrain’, ‘menacing skies’, ‘chattering birds’ – this identification is carried to an extreme in Croissant-Rust’s prose. Natural forces appear to have co-opted our motives and our means, and are engaged in a continual battle among themselves, a quest for supremacy, in which humans are reduced to collateral. It is the rocks, the clouds, the winds, the waters and the sun that claim agency. We, instead, are acted upon, prey to capricious forces, too dim to even remove ourselves from the path of their onslaught. The image of the dance is key; the dance of death, but also the dance of dead (inanimate) objects. So while people dance – most notably in the infernal ‘Ball’ – more often it is the choreography of objects that Croissant-Rust records – sunbeams, clock hands, will-o’-the-wisps, snowflakes, as well as the malevolent, shadowy shapes of ‘Industria’.

In this edition

Death (set of short stories originally published as Der Tod: Ein Zyklus von siebzehn Bildern in 1914; copyright 1913)

Prose Poems (set of short pieces originally published as Gedichte in Prosa, 1893)

Afterword by the translator, James J. Conway