In honour of Women in Translation month we are presenting a previously untranslated piece from the last chapter of Else Lasker-Schüler’s career. ‘Etwas von Jerusalem’ (A Little about Jerusalem) appeared in February 1940 in the short-lived Jüdische Welt-Rundschau, a weekly German-language newspaper established in Palestine by Jewish refugees who had fled Nazi Germany following Kristallnacht. Printed in Paris, it launched in 1939 – the year Lasker-Schüler settled in Jerusalem, having been refused re-entry to Switzerland – but was discontinued when the Nazis occupied France in May of the following year.

Although by now old, poor and isolated, Lasker-Schüler continued to write throughout her Jerusalem exile; three of the four local newspapers she mentions in ‘A Little about Jerusalem’ ran her work. The piece was part of a projected book which she never finished, initially titled Tiberias and later Die Heilige Stadt (The Holy City). The partly handwritten, partly typed manuscript is held by the National Library of Israel, along with a yellowing copy of the original Jüdische Welt-Rundschau article.

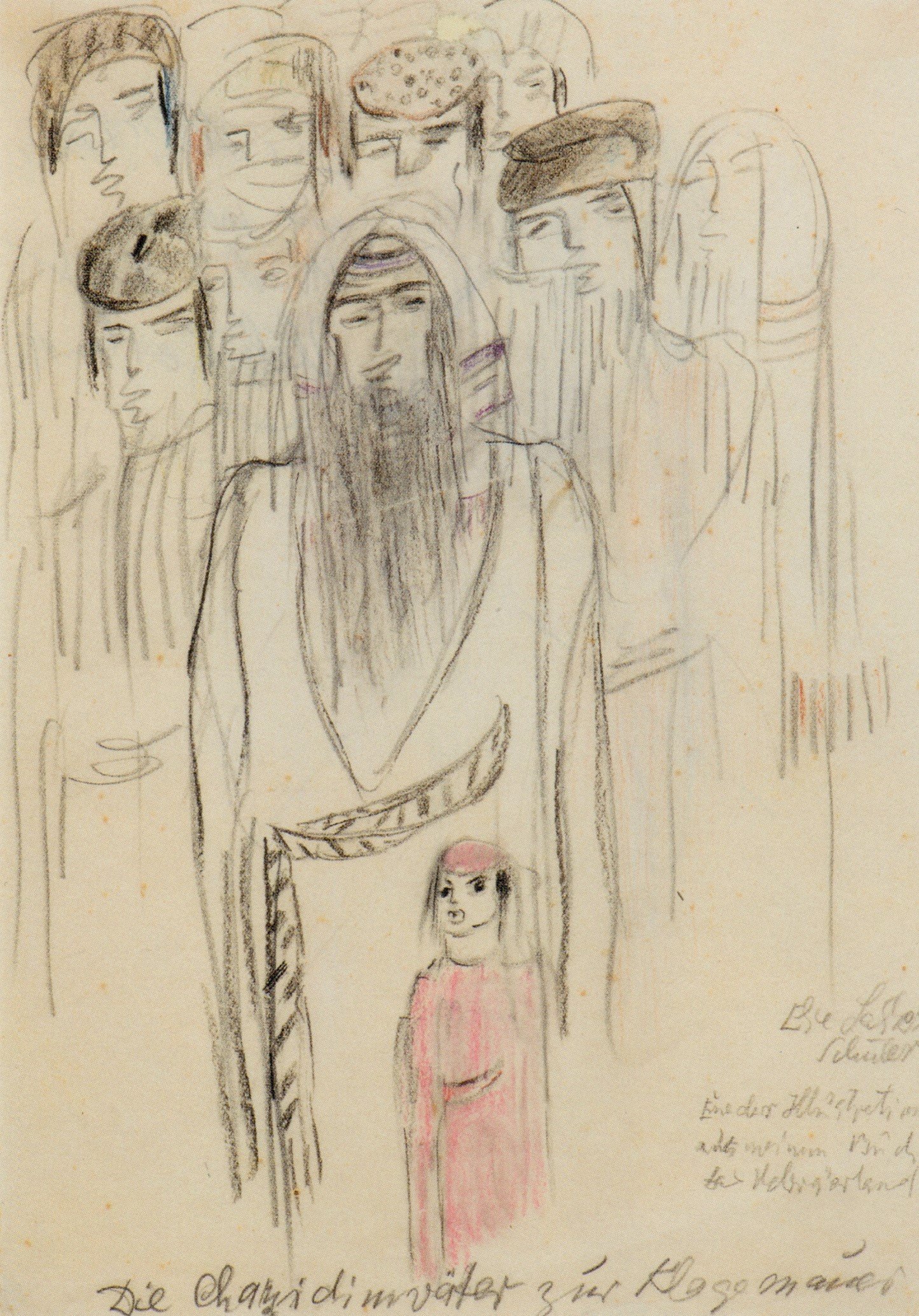

This is a particularly enlightening piece because it offers a lived counterpoint to the imagined ‘Orient’ Else Lasker-Schüler presents in two of our Three Prose Works: The Nights of Tino of Baghdad and The Prince of Thebes, whose final scene sees the author’s alter ego, a ‘princess of Baghdad’, leading an army in Jerusalem. Here, awakened from the Orientalist reverie of her early 20th-century prose by the shock of reality, she undergoes a process of dis-orientation. Certainly the digressive flânerie of the text is something of an anomaly in Lasker-Schüler’s writings. It is striking that in the numerous prose works she wrote during the almost four decades she spent in Berlin, for instance, she rarely examined the city itself at any length. But perhaps the dislocation of her new surroundings was simply so overwhelming that it activated her receptive faculties. So too with the visual art she produced during this period (including the images presented here), where observation generally trumped imagination.

The idiosyncratic Jewish mysticism evident in ‘A Little about Jerusalem’ finds extensive precedent in the writer’s work, yet here she seems more inclined to seek God in nature. Having only ever lived in central city settings (as she herself notes), she divines the divine in the labours of the kibbutzniks. Lasker-Schüler – who always emphasised the Semitic, the commonalities of Jewish and Arab cultures – provocatively refers to the imposing modernist arc of the Jewish Agency headquarters as a ‘crescent moon’, but she cannot ignore the widening gap between ethnic groups in Mandatory Palestine. Her wanderings become a prayer for reconciliation of the opposed and protection of the weak – the overtaxed beasts of burden and the children living in poverty.

Contemplations of the Holy City appear in Lasker-Schüler’s very earliest writings. In the 1901 verse ‘Sulamith’ she writes of ‘burning up in the evening colours of Jerusalem’. This was decades before she first visited the city, at a time when actually living there would have been unthinkable. But here she is, in 1940, exploring the city at the side of her rabbi friend, Kurt Wilhelm, writing the last chapter of her life; her ecstatic, apocalyptic early verse is revealed as prophecy as she contemplates the purple sky of Jerusalem, the ‘heart of the Eternal’. ‘What I never thought I would see even in dreams was actually fulfilled at the ends of the earth.’

Five years later Kurt Wilhelm officiated at the funeral of Else Lasker-Schüler on the Mount of Olives.

Else Lasker-Schüler

A LITTLE ABOUT JERUSALEM

translated by James J. Conway

I wander aimlessly … along Jaffa Road via King George Street to Rehavia. Pass the beautiful Jeshurun synagogue, and wonder, should I climb the little mound where that pious jewel is shimmering now? Or should I make directly for my destination, the House of Keranot and the Jewish Agency? In my first book, The Land of the Hebrews, I likened the beautiful building of this Hebrew ministry to a rabboni lovingly receiving pilgrims in his arms. Built on the model of the crescent moon, from a distance the magnificent house seems to be waxing and waning, cast in the ebullient reddish-yellow light of the evening hour. – In the anteroom of the mighty palace sits a tender Jewish man-in-the-moon, extending the same protection to all. A simple, bearded guard. He already knows – I want to see dear, tireless Gveret Caraway.

I have come from the middle of the city of Jerusalem. I love living in the middle of the city in every city and – especially in Jerusalem! To hide snug behind the hedges somewhere, for me that would be like taking refuge from events. I don’t want to miss out on things refreshing or painful, neither suffering nor the sudden radiant smile of a child receiving a gift. Nor the sight of the adorable, busy little newspaper boys: ‘Haaretz! ‘Davar!’ ‘Palestine Post!’ ‘Tamzit Itonejnu!’ I have taken these sweet adonai, budding big-time merchants already, to my heart. And I feel proud if at least one of them is sitting on the steps of our hallway, confidently waiting for me. We used to like sweets as well, didn’t we?!

May I never miss a single event, a sound, a footstep or a hoof! No donkey, still less a caravan of camels, crosses the Jaffa Road unseen by me. And I often answer the question: why don’t I live in Rehavia, or in another suburb of Jerusalem? with an excuse – which is not entirely untrue. You can’t just eat green sweetmeats all day!

Yet right now I love the trees beyond words, they are kin to me like the brook. So many people are reflected in my face.

Even birds dwell with me in the surging city of Jerusalem, and they are free, invited by their leafy great-grandmother to dwell among shady branches in the gardens of Rehavia. There is still so much green there!:

And should you plant me like a tree,

A carob tree then I would be.

And there I would await with glee,

The month of May, month of May!

Here in Asia, where less is evergreen, those transplanted to Palestine seek their leafy places with greater honesty and ardour. Indeed, what you lack or lost! On the other hand, the farmers among the Jews, the princes of Jeshurun, prefer to visit the heart of the Holy City, only to return home late in the evening to their fields and groves, tangled in their roots, children of Israel who are pleasing to God. These farming communities open up the testament of the rusty earth, and enliven the yellowing layers of the soil. We who visit Emek merely leaf through the pages of the soil. I blush …

These godly tillers encounter God when their shovels strike the soil of each new settlement. This great wordless devotion pleases Adonai. Surely God is not a vain God, a vain father who only brought His children unto the world that they may praise Him with words? The Lord Himself was a divine farmer who planted the first cypresses and the pomegranates; entrusted the vine seedling to Noah, the vintner. Above all, God sowed THE HEDGE OF MERCY around the city of Jerusalem so dear to Him.

Camels, noble kings, trot across the high road once more. I feel the urge to honour them, to linger a few moments. Between mound and mound of the noble desert animals sits the Bedouin in a striped satin cloak, his young son safely before him. When he grows up, Sarah’s children and Hagar’s descendants will shake hands like siblings. Maybe even tomorrow, or tonight beneath the heavens. For in the darkness many heavens hover down on wings; angels in downy powder blue and lilac feather cloaks. And facing the Godly East a second Heaven: a wide wing of fire spreads over the bridal city of the Lord … ‘Comfort us Jerusalem and each of us the other encountered devoutly along the way. Open your gates to all who beseech entry!!’

OR IS IT GOD HIMSELF WHO MUST OPEN THE GATES?!

Stroke the beast, your donkey, who tirelessly carries the stone for building. They are often overburdened, and their choking cries wound my heart. Be gentle with the merest beast – yet though you savour its flesh.

The man of the Orient, Jew and Arab, knows the camel that bears him is a faithful friend. Above all, take care of the defenceless starving child. WITH EVERY CHILD, GOD GROWS ANEW ON EARTH!

The great-grandchildren of Abraham shake hands, perhaps right now, for I yearn for it with all my heart, with all my spirit and with all my might.

Sons of Allah encountered anew, great striking figures; and Arab women striding proudly in the upper town on the Jaffa Road; carrying their sweet little children or baskets of fruit on their heads, as they have since antiquity. And I look in the shop windows of the streets alongside the veiled harem dwellers in black robes and slender ankle boots.

The inhabitants of Jerusalem sleep a lot and lay down to bed in the early evening. They sleep through small disputes, but also fierce enmities and – above all – those of artificial origin. I like to descend into the Arab part of town and look at the houses from the age of the Maliks in the heady, colourful streets and alleys.

It is to the tirelessly cordial Rabbi Doctor Kurt Wilhelm here in Jerusalem that I owe my actual excursion down to the Arab part of the city, two years ago. Three years previously I had lit a loving candle on the way to the divine Wailing Wall, the Wall of Mercy. But today I owe the sight of the lower city, which is closer to heaven, to the spiritual doctor, whose sermons and teachings are as honest and enlightened as he himself, free of cinders and superstition. My eternal thanks to him, that I saw the City of David yet diamond bright. In the innermost part of the old town, houses coil into each other fathoms deep. Houses become siblings in the depths of the earth. We enter the house where Luria was born. The childhood home of Jeshurun’s holiest, most devout rabboni. I sit in the little niche where the saint slept his first slumber.

Back in the upper part of Jerusalem, shaken, and intoxicated by the burgundy sun, I collapsed. What I thought I would never see, even in dreams, actually transpired at the ends of the earth.

The sky shone purple like today, we looked to the feast day sky, into the heart of the Eternal – wide open for all – God and His angels all about … The doctor relates the miracles of the Bible in the open air – while the flourishing tall cypresses, the verdant Torah toys with the stars.

‘A Little about Jerusalem’ was first published in German as ‘Etwas von Jerusalem’ in the Jüdische Welt-Rundschau, Volume 2, No. 6, 12 February 1940.

This translation © 2022 James J. Conway