Magnus Hirschfeld’s 1904 report Berlin’s Third Sex – probably the first sympathetic account of gay and lesbian city life ever published – is a remarkable enough book in its own right. But in fact it was just one part of a much larger project. The Großstadt-Dokumente, or Metropolis Documents, of which Hirschfeld’s book was the third instalment, were issued by the Hermann Seemann publishing house between 1904 and 1908. In all there would be 51 volumes, together representing one of the most far-reaching studies of urban existence ever undertaken, a vast portrait of the city at the outset of the 20th century. And around three quarters of the titles were about one city in particular: Berlin.

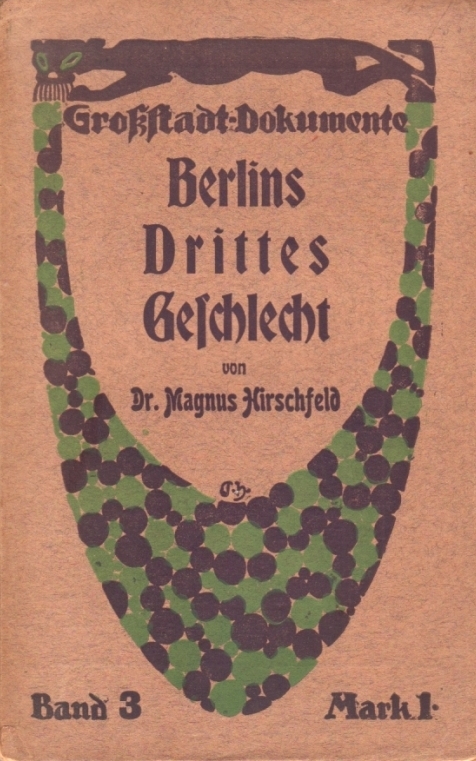

The original German edition (1904) of Berlin's Third Sex

The books appeared at an astonishing rate (up to 16 in a single year) and were printed on cheap stock to be sold at the price of one mark – significantly less than the average paperback of the time. Later they were issued in hard cover thematic anthologies of five volumes apiece. They were the brainchild of Berlin-born writer Hans Ostwald (1873-1940), and reflected his enormous interest in the society around him, particularly those of its members who stood outside the mainstream – including bohemians, prostitutes, cult followers, socialists, petty criminals, vagabonds, unwed mothers and juvenile delinquents. Each book addressed a different phenomenon of urban life. Five of the titles were by Ostwald himself, while the 39 other writers he chose were typically young, male journalists of his acquaintance, few of whom found lasting renown. The sole female author, Ella Mensch, used her platform to attack what she regarded as overly radical elements in the women’s emancipation movement.

Hans Ostwald

It all began with Ostwald's own Dark Corners of Berlin (1904), which took the reader to dive bars, homeless shelters and other haunts of the down and out ordinarily invisible to the bourgeois reader. Subsequent volumes blended reportage, polemics and sensationalism, and while they certainly pushed at the limit of what Wilhelmine Germany would allow, only one volume was actually banned from sale – Germany’s first major study of lesbianism, written by Wilhelm Hammer. But even the less contentious titles revealed parts of the city readers might never otherwise encounter, including court rooms, sweatshops and the offices of public servants. The last of the Metropolis Documents was Edmund Edel's Neu-Berlin (1908), a stroll amid the bright lights and consumerist revelry of the Ku’damm and other gathering places of the moneyed bourgeoisie in the rapidly expanding city.

Rixdorf Editions' collection of Metropolis Documents anthologies

Even within Germany this remarkable series excites little recognition beyond academic circles, in contrast to the broad, educated readership Ostwald originally had in mind (any German-speakers who wish to find out more are directed to Ralf Thies’s exhaustively researched 2006 book, Ethnograph des dunklen Berlin). Berlin’s Third Sex is the first of the titles to appear in English and considering how much these books tell us about Berlin at the outset of the century it would define like no other, it is remarkable that over 100 years later the Metropolis Documents are all but unknown to Anglophone readers.