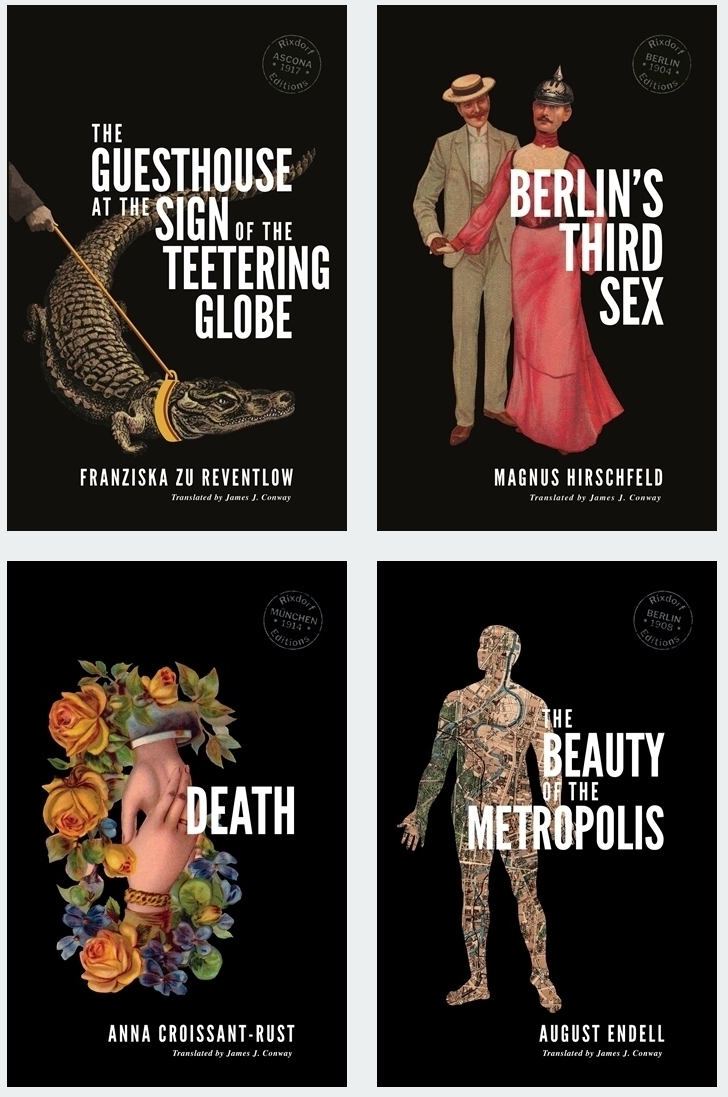

With our forthcoming publication The Nights of Tino of Baghdad, we though it would be interesting to share a short piece by the author of that work, Else Lasker-Schüler, in which she discusses her friend Magnus Hirschfeld, author of Berlin’s Third Sex.

This is one of numerous pen portraits of her friends and associates – including Karl Kraus, Oskar Kokoschka, Gottfried Benn, Tilla Durieux and Alfred Kerr – that Lasker-Schüler produced throughout her career, prose miniatures that capture the essence of her subjects’ personae. This article was first published toward the end of the First World War, and takes the form of an open letter to university students in Zurich where Hirschfeld was shortly to give a lecture. Describing his 50th birthday party which had taken place a few weeks earlier, it presents a warmer, more playful side to the tireless activist and pioneer of sex studies than most other accounts, including his own autobiography.

Else Lasker-Schuler

Doctor Magnus Hirschfeld

translated by James J. Conway

On Thursday, 11 July you will hear Magnus Hirschfeld speak in Zurich at the Schwurgerichtssaal; it is an evening to which you can look forward. I should like to tell you something about our doctor in Berlin. He is not just our doctor, he is also our host; his consultations end in beaux jours, the ailing forget their neuroses and for the healthy patient an afternoon in his delightful waiting rooms provides pleasing stimulation for the nerves. There in the middle of the Tiergarten amid stout chestnut trees and whispering acacias lives Medical Councillor Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld. Not that he likes us calling him that. ‘Children, just call me “Doctor”.’ Nevertheless, he confessed to me that his appointment to the Medical Council on the occasion of his fiftieth birthday, greatly disputed and contested among the medical profession though it was due to his exceptional position, had pleased him. Beaming like a child, he showed me all his presents. We call him our doctor. And unto our doctor my playmates and I delivered an exquisite serenade on the eve of his birthday revels. Touched, the revellers came out onto his balcony to hear our songs accompanied by accordion and drum. The concluding chorus: ‘I should like to carve it in every crust...’. He is amused by our exuberance, because – being earnest – Dr Hirschfeld understands jest, he is not some serious professor with an oak-leaf beard. Now, I must confess to you dear students that, to my shame, I am not familiar with any of the many famous books that the doctor has written (essentially I only read my own), but can nevertheless judge them from his incomparably interesting lectures, these thrilling medical, historical novels, standard works that never turn stale. Doctor Hirschfeld is the advocate of sincere love of any kind, opponent of all forms of hatred. A gentle forensic physician who seeks to understand everything. All compassion, he sacrifices his strength, his time, his good heart to the departing soldier. At the railway stations one often sees our doctor cultivating entire tobacco plantations, distributing numerous boxes of cigars and cigarettes as he farewells them in their field grey. He is a man whose goodwill is truly blind to class. He rushes to those who summon him. I once ambushed him myself, and managed to get him away from his great practice to accompany me to a wounded friend in Pomerania. Gentlemen, I am pleased to sing the praises and wonders of our Doctor Hirschfeld. When he is away from Berlin it is as though our father confessor were missing. We all long for his words of comfort, for his cosy, warm green chambers which are as soothing as the man himself.

‘Doktor Magnus Hirschfeld’ by Else Lasker-Schüler was first published in German in the Züricher Post und Handelszeitung, 10 July 1918. First book publication in Essays, published by Paul Cassirer, 1920.

This translation © 2019 James J. Conway