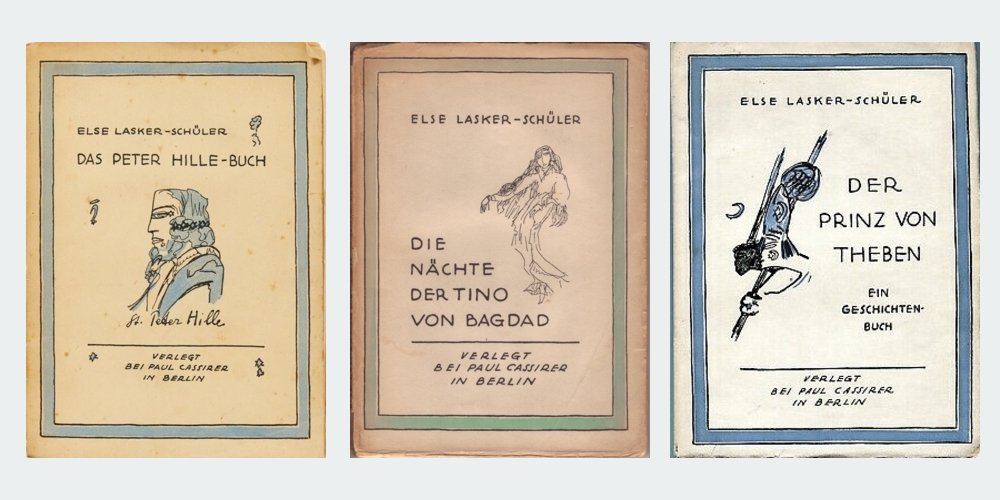

One of the many fascinating things about Else Lasker-Schüler’s career is that through her dynamic, luminous illustrations, we have an insight into how she herself saw the characters who appear in her writings. In particular, the biblical figure of ‘Jussuf’ (Joseph/Jusuf, the favoured son of Jacob with the coat of many colours) looms large over both her graphic and written work. As the afterword to Three Prose Works reveals, Joseph was a persona of life-long identification for Else Lasker-Schüler, one that connected her to her brother Paul and her mother Jeanette, the two family members to whom she was closest. Paul taught the young Else the story of Joseph and his brothers, which she would in turn act out for her mother. Joseph was also associated with her early socialisation; when she told the story at school, a classmate mockingly declared that Else was Joseph.

That more or less came true shortly before the First World War; in a distressing phase of transition he became an alter ego to the writer and artist, although she fused the biblical figure with a fictional ‘Prince of Thebes’. This hybrid character not only turned up in Lasker-Schüler’s writing (most notably of course in The Prince of Thebes, issued in 1914 – the third of our Three Prose Works) but also her correspondence and numerous artworks. These images constitute a rich iconography spanning over 20 years, reappearing throughout the Weimar Republic and later accompanying Lasker-Schüler into exile.

Pre-World War One

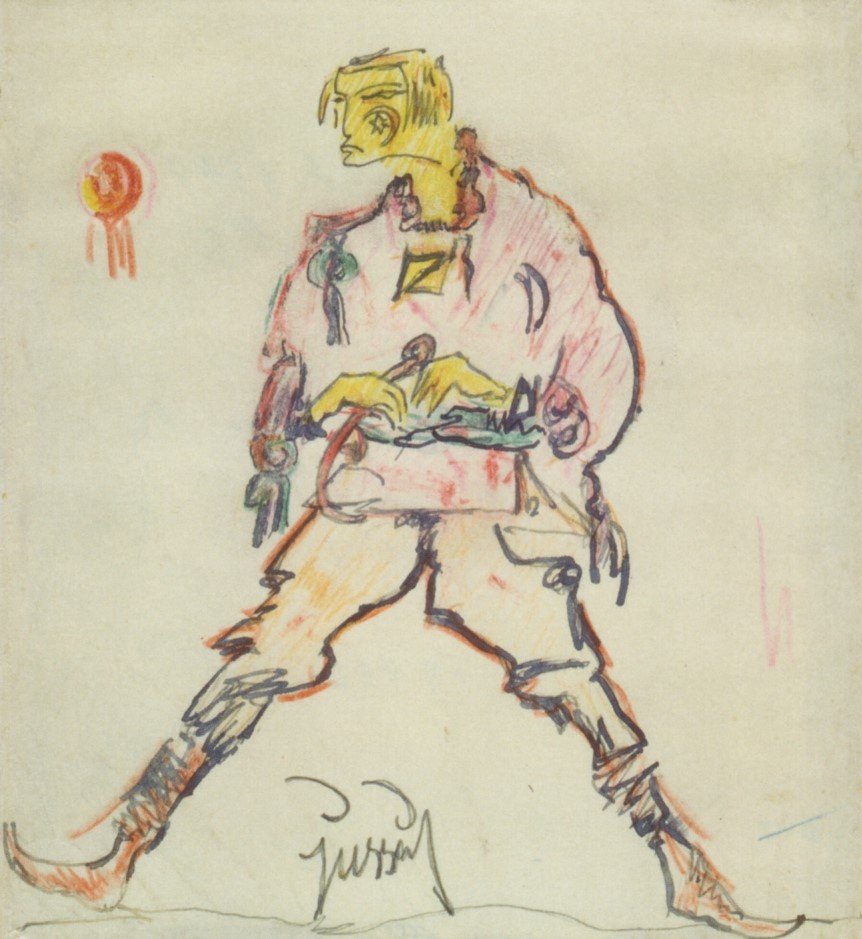

It was in 1912, triggered by her painful split from second husband Herwarth Walden, that Else Lasker-Schüler reached back and reconnected with Joseph (Jussuf)/Prince of Thebes. The ‘self-portrait’ that adorned an edition of the journal Saturn the following year is a kind of ‘coming out’ of the writer’s new persona. He is shown in profile, as he would be in the majority of later images as well. He is frequently accompanied by a crescent moon or a Star of David, or more often both – shorthand for the Semitic realm in which Lasker-Schüler places her prince (see for example the cover of The Prince of Thebes, 1914). The images themselves are sometimes rendered in a few strokes which emphasise a strong brow and down-turned mouth which he shares with his creator. Once fixed, these features remained remarkably consistent.

In a postcard to Georg Trakl, sent a few months before the war which would claim the doomed poet in its early stages, we see how Jussuf/Prince of Thebes appears in Lasker-Schüler’s correspondence. For the rest of her life she often signed her letters with some variant on these names.

1913 | An edition of the journal Saturn entirely dedicated to Lasker-Schüler’s work

1913 | ‘The Prince of Thebes heads into holy battle’

1913 | ‘Jussuf Prince Tiba’

1913 | Self-portrait as Prince Jussuf

1913/14 | ‘Jussuf with spear’

1914 | Postcard addressed to Georg Trakl

Weimar Republic

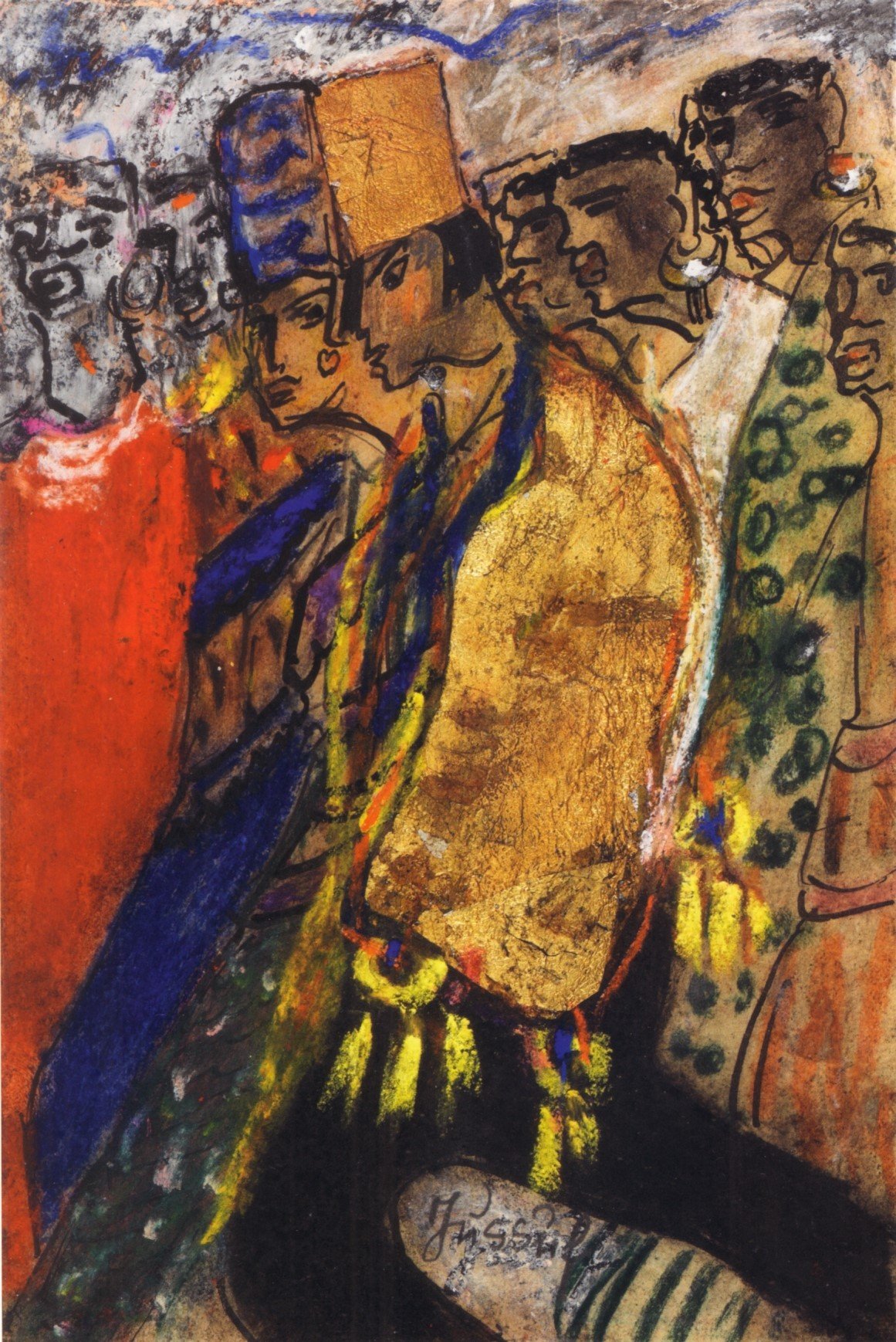

During the First World War, Else Lasker-Schüler exhibited her art for the first time, and her work in the 1920s signals her confidence as a visual artist. Jussuf recurs throughout the Weimar period, although in contrast to the martial figure of the pre-war era the depictions tend to emphasise his sensitivity. He is often paired with animals (recalling his original role as a shepherd) and in one depiction the prince admires a blue rose, blue being an emotionally charged colour in Lasker-Schüler’s world. In the 1920s he appears more often in full length, a lithe physical presence, and the treatments advance from the pen sketches that dominate early depictions to more elaborate, appropriately many-coloured images in paint and even gold leaf.

Jussuf appears in different forms in the 1923 volume Theben, arguably the consummate union of Else Lasker-Schüler’s words and images. It featured hand-written verse in facsimile accompanied by illustrations, with 50 copies additionally hand-coloured by the writer/artist herself (even the uncoloured editions can sell for around EUR 10,000 these days). Theben was issued by the publisher Querschnitt, which was owned by the prominent gallerist Alfred Flechtheim – a key figure in the dissemination of Modernism in Germany.

1920 | ‘Asser Memed Schalomein Jussuf’

1920 | ‘Jussuf sculpts his mother’

1921 | ‘This is Jussuf in the evening full of longing’

1922 | ‘Thebes with Jussuf’ (from the book Theben, 1923)

1923 | ‘Jussuf goes to God’ (from the book Theben, 1923)

1927 | ‘Jussuf’

1927 | ‘Jussuf tending the goats in pasture’

1927/28 | ‘Elephant with Jussuf’

Exile

Else Lasker-Schüler left Germany in April 1933, shortly after the Nazi takeover. Despite the penurious conditions under which she endured exile in Zurich, and later Jerusalem, she continued to write and produce art. An unusual image from 1935 returns us to the word, with Jussuf – in something like Western costume – reading his verse. The final sketch, which shows Jussuf praying for peace, is undated but may have been created around the beginning of Else Lasker-Schüler’s residency in Jerusalem, at the outbreak of the Second World War.

1934 | ‘Prince Jussuf of Thebes’

1935 | ‘Prince Jussuf reads his verses aloud’

1939(?) | ‘Prince Jussuf prays for peace in the world’