Our translation of Else Lasker-Schüler’s The Nights of Tino of Baghdad is prefixed with the words: ‘This book I give to my beloved playmate, Sascha (Senna Hoy)’. At least, this is the dedication in the 1919 second edition that formed the basis for our translation; the first edition from 1907 was dedicated to the author’s mother.

So who was Sascha, a.k.a. Senna Hoy? Behind these names was a man born in 1882 with the far less exotic handle of Johannes Holzmann. But it was as ‘Senna Hoy’ – a phonetic reversal of his first name bestowed by Lasker-Schüler herself – that the German-Jewish bohemian anarchist writer found a measure of fame, or at least infamy. The extraordinary image above appears to be the only photograph of him that has survived, but it offers a vivid sense of a man whose zeal, magnetism and rebellious spirit made a great impression on his contemporaries. It remains a mystery why no one has yet undertaken a biography of this enormously compelling character.

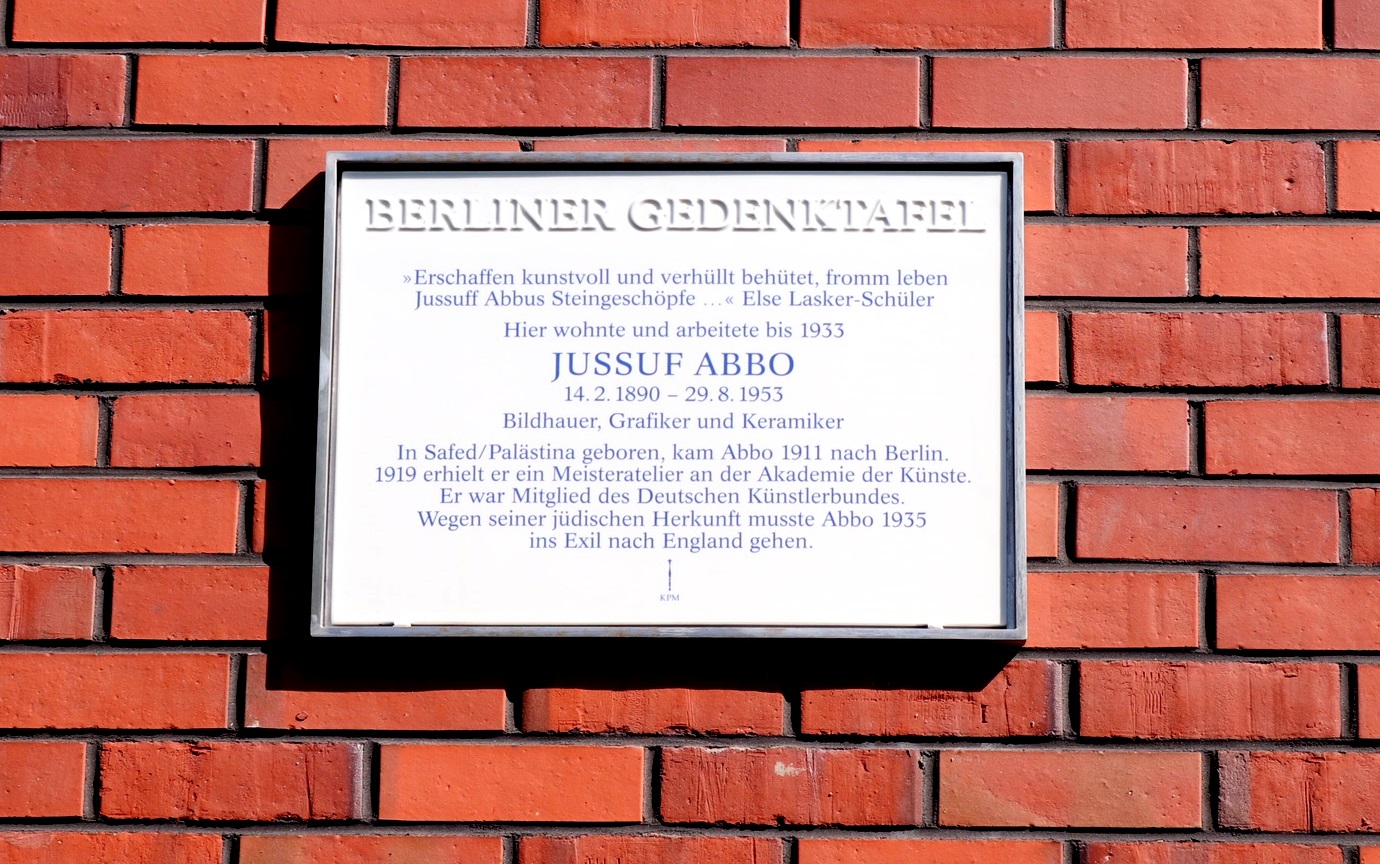

Senna Hoy was a member of the ‘Neue Gemeinschaft’, or New Community, which greeted the dawn of the 20th century with grand plans for society from their base in Schlachtensee, a lakeside district then south-west of Berlin’s city limits. It was here that Else Lasker-Schüler made numerous vital contacts as she embarked on a new life, having recently separated from her first husband, Berthold Lasker. She was particularly drawn to the handsome young Holzmann in a group that also included the reform-minded artist Fidus (born Hugo Höppener), the philosopher Martin Buber, radical activitist Erich Mühsam, anarchist pacifist Gustav Landauer, writer and part-time vagrant Peter Hille, as well as Georg Lewin, who would become Lasker-Schüler’s second husband and a vital catalyst for early modernism in Germany under the name Herwarth Walden – also an invention of his wife.